Moraines are distinct ridges or mounds of debris that are laid down directly by a glacier or pushed up by it 1 . The term moraine is used to describe a wide variety of landforms created by the dumping, pushing, and squeezing of loose rock material, as well as the melting of glacial ice.

In terms of size and shape, moraines are extremely varied. They range from low-relief ridges of ~1 m high and ~1 m wide formed at the snout of actively retreating valley glaciers 2 , to vast ‘till plains’ left behind by former continental ice sheets 3 .

Moraines consist of loose sediment and rock debris deposited by glacier ice, known as till. They may also contain slope, fluvial, lake and marine sediments if such material is present at the glacier margin, where it may be incorporated into glacial ice during a glacier advance, or deformed by glacier movement 4,5 .

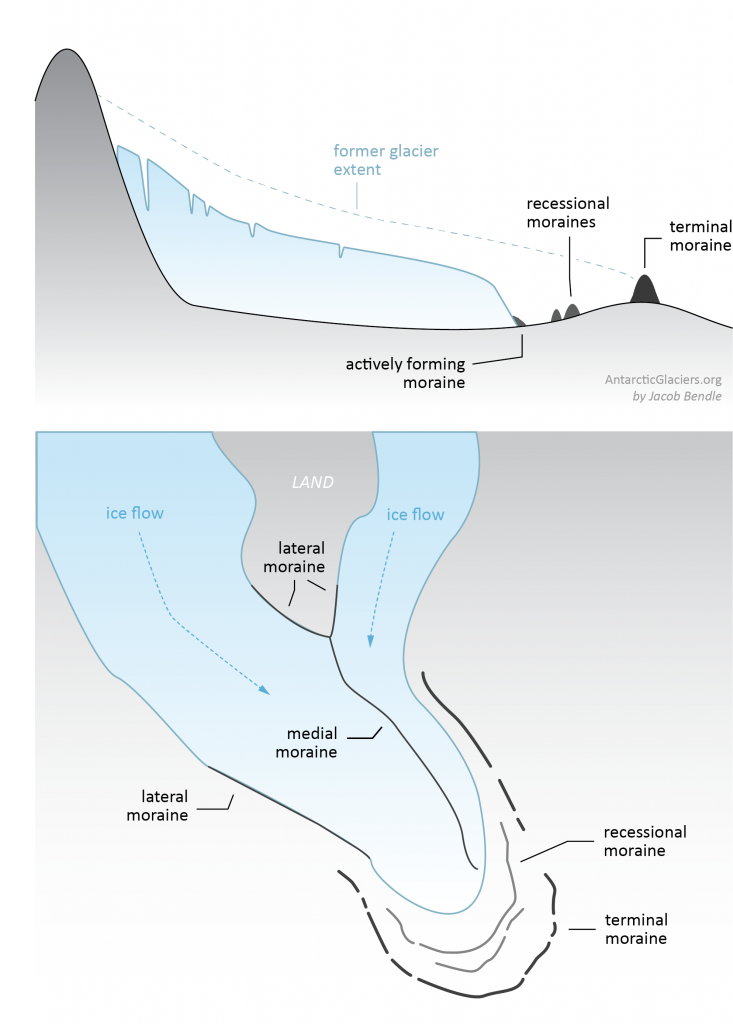

Moraines are important features for understanding past environments. Terminal moraines, for example, mark the maximum extent of a glacier advance (see diagram below) and are used by glaciologists to reconstruct the former size of glaciers and ice sheets that have now shrunk or disappeared entirely 6 .

The most common moraine types are defined below:

A terminal moraine is a moraine ridge that marks the maximum limit of a glacier advance. They form at the glacier terminus and mirror the shape of the ice margin at the time of deposition. The largest terminal moraines are formed by major continental ice sheets and can be over 100 m in height and 10s of kilometres long 7,8 .

Recessional moraines are found behind a terminal moraine limit and form during short-lived phases of glacier advance or stillstand that interrupt a general pattern of glacier retreat. In some cases, recessional moraines form on a yearly basis (normally as a result of winter glacier advances) and are known as annual moraines 9,10,11 .

Lateral moraines form along the glacier side and consist of debris that falls or slumps from the valley wall or flows directly from the glacier surface 12 (see image below). Where the rate of debris supply is high, lateral moraines can reach heights of more than 100 metres 12–15 .

The term latero-frontal moraine is used where debris builds up around the entire glacier tongue 14 . These moraine types are common in mountain settings such as the European Alps, the Southern Alps of New Zeland (see the Mueller Glacier moraines below) and the Himalayas, where the high supply of rock debris from unstable valley sides, rapidly build up at the glacier margins.

Medial moraines are debris ridges at the glacier surface running parallel to the direction of ice flow 4,5 . They are the surface (or supraglacial) expression of debris contained within the ice. Medial moraines form where lateral moraines meet at the confluence of two valley glaciers, or where debris contained in the ice is exposed at the surface due to melting in the ablation zone 16 .

Ground moraine is a term used to describe the uneven blanket of till deposited in the low-relief areas between more prominent moraine ridges 6 . This type of moraine, which is also commonly referred to as a till plain, form at the glacier sole as due to the deformation and eventual deposition of the substratum.

1. Hambrey, M. J. 1994. Glacial Environments. UCL Press.

2. Krüger, J., Schomacker, A. and Benediktsson, Í.Ö., 2010. 6 Ice-Marginal Environments: Geomorphic and Structural Genesis of Marginal Moraines at Mýrdalsjökull. Developments in Quaternary Sciences, 13, 79-104.

3. Dyke, A.S. and Prest, V.K. 1987. Late Wisconsinan and Holocene history of the Laurentide Ice Sheet. Geographie Physique et Quaternaire XLI, 237–63.

4. Benn, D.I. and Evans, D.J.A., 2010. Glaciers and Glaciation. Hodder Education.

5. Bennett, M.M. and Glasser, N.F. 2011. Glacial Geology: Ice Sheets and Landforms. John Wiley & Sons.

6. Schomacker, A. 2011. Moraine (Eds.) Singh, V.P., Singh, P. and Haritashya, U.K. Encyclopedia of Snow, Ice and Glaciers. Springer.

7. Dyke, A.S., Andrews, J.T., Clark, P.U., England, J.H., Miller, G.H., Shaw, J. and Veillette, J.J., 2002. The Laurentide and Innuitian ice sheets during the last glacial maximum. Quaternary Science Reviews, 21, 9-31.

8. Glasser, N.F., Jansson, K.N., Harrison, S. and Kleman, J., 2008. The glacial geomorphology and Pleistocene history of South America between 38°S and 56°S. Quaternary Science Reviews, 27, 365-390.

9. Sharp, M., 1984. Annual moraine ridges at Skálafellsjökull, south-east Iceland. Journal of Glaciology, 30, 82-93.

10. Bradwell, T., 2004. Annual moraines and summer temperatures at Lambatungnajökull, Iceland. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 36, 502-508.

11. Beedle, M.J., Menounos, B., Luckman, B.H. and Wheate, R., 2009. Annual push moraines as climate proxy. Geophysical Research Letters, 36.

12. Lukas, S., Graf, A., Coray, S. and Schlüchter, C., 2012. Genesis, stability and preservation potential of large lateral moraines of Alpine valley glaciers–towards a unifying theory based on Findelengletscher, Switzerland. Quaternary Science Reviews, 38, 27-48.

13. Benn, D.I. and Owen, L.A., 2002. Himalayan glacial sedimentary environments: a framework for reconstructing and dating the former extent of glaciers in high mountains. Quaternary International, 97, 3-25.

14. Benn, D.I., Kirkbride, M.P., Owen L.A. and Brazier, V. 2003. Glaciated Valley Landsystems (Ed.) Glacial Landsystems, Arnold, London.

15. Evans, D.J., Shulmeister, J. and Hyatt, O., 2010. Sedimentology of latero-frontal moraines and fans on the west coast of South Island, New Zealand. Quaternary Science Reviews, 29, 3790-3811.

16. Eyles, N. and Rogerson, R.J., 1978. A framework for the investigation of medial moraine formation: Austerdalsbreen, Norway, and Berendon Glacier, British Columbia, Canada. Journal of Glaciology, 20, 99-113.